Lot n°61

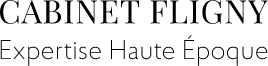

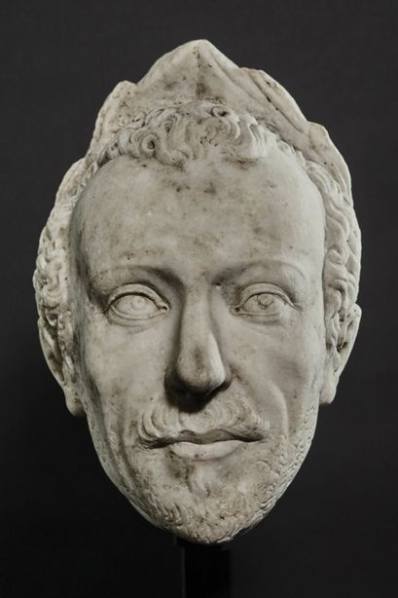

Importante tête d'homme laurée

Adjugé 300 000 €//fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jules_Delpit

A rediscovered sculpture by Germain Pilon possibly the head of Jacques de Lévis-Caylus, the best known of Henry III of France's favourites known as the «Mignons»

Important head of a man crowned with a laurel wreath, Carrara marble sculpted in the round.

A portrait of a young man with a somewhat gaunt face featuring a high, domed forehead, a long, straight nose, a mouth with finely drawn lips, a trimmed moustache and beard; open eyes with semi-circular upper palpebral fold, lashed eyelids with visible lacrimal caruncle, irises positioned beneath the upper eyelids, circumscribed by an incised line and with pupils centred on a point; forehead with exposed temples surmounted by curly hair; severed neck with chisel marks, revealing the cavity from a lead fixing.

Île de France, Paris, Germain Pilon (known 1540-died Paris 1590), after 12 July 1578/first half of 1579.

H_34 cm

On plinth.

(some light abrasion, tip of the nose restored)

An export certificate of the lot will be given to the buyer

Provenance:

- Ex-collection Jules Delpit (1808-92), Bordeaux

- Ex-collection, private, Bordeaux region

A head of such dimensions, that is to say over life-size, sculpted in extremely costly Carrara marble and, moreover, wearing a laurel wreath, could only be that of an illustrious figure connected with the court of around 1580. Indeed the physiognomy of the face links it to the reign of Henry III: the highly pronounced lobes above the temples, the curly, swept-back hair, the short, well-trimmed beard, the high cheekbones and the pointed chin recall the portrait of the monarch after Nicolas Hilliard, circa 1578 (fig. a).

This is evidently a portrait because despite being mildly idealised, the features remain individual, hence the pronounced lines of the cheeks, the distinctive development of the frontal bone, the vivacity of the gaze and the marked sensuality of the mouth. While possessing the character of youth, this face gives a strong impression of determination and daring.

The laurel wreath is a mark of distinction uncommon in sculpted portraits of the sixteenth century. It can, of, course, be found gracing the brow of monarchs such as the

Louvre bust of Henry II, completed between 1574 and 1579, and the equestrian statue of Charles IX in the same museum. Another example is the bronze bust of Henry III in the Wallace Collection, attributed to Germain Pilon. And to judge by the inventory drawn up after the death of this great French sculptor, in which a bronze head of a Religieux couronné de laurier is mentioned, the same honour seems to have been conferred on various prelates.

But what young person might be depicted wearing a laurel wreath? Clearly it could only be a personage belonging to the innermost royal circle, someone cut down in the prime of life in circumstances regarded as remarkable at the time. Only the favourites of Henry III known as the «Mignons» combine these qualities. This leads us to the notorious Duel of the Mignons of 27 April 1578, which claimed the lives of two of these, Maugiron and Schomberg, the same day, a third, Ribérac, the following day, and Caylus after exactly thirty-three days, when he eventually succumbed to his injuries. A few weeks later another favourite, Paul Stuart de Caussade de Saint-Mégrin, lost his life, in all likelihood murdered on the orders of the Duke of Guise.

It is known that the king was greatly affected by all of these deaths. To honour the memory of his closest favourites and in the intention of establishing a veritable cult in their name, he commissioned three tombs from his master sculptor, Germain Pilon, in July 1578.

The Tombs of the Mignons:

This commission given to Pilon by Henry III was the only one of its type and unfolded in two stages. An initial order was signed on 12 July 1578 for the tombs of Maugiron and Caylus but this was cancelled soon after, when the king decided to commission a third tomb for Saint-Mégrin. It had been agreed in the first contract that "Pillon has promised and promises to complete the aforementioned two sculptures and to deliver them in a perfect state" by the last day of December [1578]. It is known from another document that on 17 January 1579, master armourer Nicolas de Charenton was receipted for providing the sculptor with items of armour belonging to the late Saint-Mégrin, no doubt so that they could be used as a model for the kneeling statue. It can therefore be ascertained that by this date the mausoleum, or at least the tomb of Saint-Mégrin, the last to have been commissioned, had not yet been completed. That of Caylus was probably already finished given that the blocks of marble had already been selected by the signing of the first contract. There is a strong likelihood that these funerary monuments were installed in the choir of the church of Saint Paul in Paris during the course of 1579. Their existence was fleeting as they were destroyed by the people of Paris some ten years later, following the assassination of the Duke of Guise and another family member on 2 January 1589. The only depiction we have of them is an engraving by Rabel of 15881 (fig. b). In the eyes of the population, and against the backdrop of the ultra-Catholic atmosphere of the day, these luxurious tombs symbolised the presence of an ostentatious impiety at the heart of a church. Their destruction followed the ritual employed in the massacre of heretics, that is to say the cutting off of all the extremities, thereby explaining the good state of conservation of the marble head. If the sculpture of the kneeling figure was indeed thrown from the top of its mausoleum, its head had almost certainly been removed beforehand.

These sumptuous tombs commissioned by the disconsolate Henry III were admired by contemporary observers. Visitors came to see them when passing through Paris.

One such was the Dutchman Arnold van Buchel, who described them as "glittering marble and bronze tombs with marvellous marble statues of the three courtiers". The model for these funerary monuments - a tapering sarcophagus resting on an entablature and supporting the statue of the deceased kneeling with hands joined in prayer before a prie-dieu - was well used by Germain Pilon but here he gives his most magnificent version of it. Due to the luxurious materials used, the first two cost the substantial sum, for the day, of 3,500 crowns. Although this initial specification was cancelled, it is highly likely that the definitive contract for the three sepulchres, now missing, incorporated the same description. What stands out from this description is the use that was to be made of white and black marble, the inclusion of numerous decorative elements, such as bronze trophies and coats of arms, as well as a number of cherub's heads in white marble. The statues that surmount each tomb are described as follows: the "deceased sires praying, life-size in white marble and as life like as can be". By contrast with the ecclesiastical world, which preferred recumbent figures, the formula that had been favoured since the 1550s by the nobility had been the kneeling figure.

The brutal deaths of these young men belonging to a group of favourites very close to the monarch, and affectionately referred to by the king himself as "ma troupe", were much lamented. A number of poets, including illustrious figures such as Ronsard, Desportes and Jamyn, as well as the official preacher to the king, Arnaud Sorbin, composed sonnets and other verse works extolling Maugiron, Caylus and Saint-Mégrin. Pierre de l'Estoile, the famous chronicler of the day, reproduces these Sonnets courtizans à la mémoire des trois mignons in his diaries. 2 Certain lines speak of the tombs and the glorious laurel wreaths crowning the heads of the departed:

Il ne fault vous douloir, soubs vos tombeaux couverts

De mirte et de laurier, que vostre ame est allée

Des esprits bienheureux habiter la vallée, Perdant trop tost la fleur de vos printemps si verts.

Germain Pilon:

Although the name Germain Pilon remains firmly associated with the tomb of Henry II, commissioned by Catherine de Médicis, at Saint-Denis, it was under the reign of Henry III (1574-89) that the sculptor executed the majority of his works. Many were later destroyed, falling victim to the numerous outbreaks of unrest and destruction resulting from the civil, religious or seditious wars. Pilon was "sculptor to the king" from as early as 1558, and ended his days as "sculptor and architect in ordinary to the king". As a complete artist, Pilon exercised his talents in a wide range of materials: bronze, terracotta, stone, alabaster and marble. In particular he excelled at working the latter, translating into marble various effects more commonly found in a malleable material. It is notably in the field of funerary art that he impresses. A striking example of his genius is the recumbent statue of Valentine Balbiani leaning on one elbow (circa 1575) conserved in the Louvre.

The tombs of the Mignons date from the most fertile period in Germain Pilon's career as a funerary artist. During the fifteen years of Henry III's reign, the monarch commissioned no fewer than fifteen funerary monuments from him. And it was not by chance that the king chose Pilon for the mausoleum of his favourites. Not only was he the most experienced sculptor in Paris, he was also the natural choice of artist to commemorate members of the royal family as well as important servants of the state.

This marble head of a man is unquestionably the work of a great sculptor. Clearly in evidence are the qualities of an artist accustomed to portrait work and skilled in individualising the features, as evidenced by the vivacity of the gaze, the delicate modelling of the lips and the sensitive rendering of the cheeks, showing the creases in the skin. A number of comparisons can be made between the treatment of certain details and known works by Pilon or his studio:

The eyes: hollowed out lacrimal caruncle (Valentine Balbiani and the cherubs on her tomb, Louvre fig. c and d, soldier in the Resurrection of Christ, fig. e)

The ears: general shape, fleshy, detached lobe (The Parcae, Écouen, fig. f, Balbiani cherub, fig. g)

The hair: the shell-like curls with trepanned centres (Balbiani and cherub fig. h and i)

Caylus:

Of the three Mignons from the tombs, this marble head would seem to belong to the kneeling figure of Jacques de Lévis-Caylus (fig. j and j')

Louis de Maugiron, the youngest, at just 18 years of age, can be eliminated because he had lost an eye to an arrow in battle, earning him the nickname "le brave (or le beau) borgne" (the brave [or handsome] one-eyed man). Of Paul Stuart de Caussade de Saint-Mégrin and Jacques de Lévis-Caylus, both born in 1554, this elongated face with exposed temples and a mildly receding chin would seem to correspond to the latter. Although the highly idealised portrait by Quesnel (fig. k), depicting Caylus beardless, bears little resemblance to the marble head, the portrait in profile by Bracquemond (fig. l) is uncannily similar in its high, domed forehead, long, straight nose, receding chin and nasolabial and jugal folds that give shape to the cheek.

The pronounced upper temple area can even be observed in the portrait by Dumontier presumed to be of Caylus as a young man (fig. m).

Jacques de Caylus was reputed to be one of the most handsome of Henry III's Mignons. In the madrigal composed by the poet Flaminio de Birague to serve as the epitaph on the tomb of the Mignons, Caylus is described as follows:

Voyez Amour depaint en Adonine face

Voyés les rares traits, d'une divinité 3

Meanwhile Ronsard engages in a dialogue, asking:

Est-ce-ici la tombe d'Amour ?

Est-ce point celle d'Adonis

Est-ce Narcisse, qui aima

L'eau qui sa face consuma

Amoureux de sa beauté vaine ?

And the answer comes:

La beauté d'un jeune printemps [repose ici]4.

And Desportes, not to be outdone, offers lavish praise:

Quelus, que la nature avoit fait pour plaisir, Comme une oeuvre accomplie, admirable et divine, Portoit Amour aux yeux et Mars en la poitrine.

Jacques de Caylus was born of an ancient family. He was the son of Antoine de Lévis-Caylus, seneschal and governor of Rouergue, a great lord loyal to the king. At the age of 18, his father entrusted him with the delivery of a missive to the future Henry III, who, a year later, during his brief reign in Poland, conferred on the youth the office of Gentilhomme de la chambre du roi (Gentleman of the King's Bedchamber). Jacques de Caylus would never again leave the circle of the king. He fought alongside or for him, for example at the Siege of La Rochelle, confronted the Protestants at the Battle of Dormans (under the command of the Duke of Guise), and was taken prisoner by the Huguenots near Brouage in 1577 and held for three months. He therefore wears the laurel wreath in just recompense for his courage and as a symbol of the glory evoked by Birague in his epitaph:

Est-ce, que vous voiez sur son arc et sa trousse

Cent lauriers, vray guerdon des guerriers généreux, Et que vous ne croyés qu'un coeur si valeureux

Puisse ploier au ioug de la Cyprine douce ?

Upon his return to Paris, Caylus became embroiled in the feuds of the various factions. As a faithful servant of the king, he accepted a challenge to a duel issued by Charles de Balsac d'Entragues the Younger, known as Entraguet, one of the Duke of Guise's men, within the context of the famous Duel of the Mignons, which was fought not far from the Porte Saint-Antoine. Caylus was accompanied by his seconds Maugiron and Livarot. Whereas Entraguet escaped virtually unscathed, Caylus was fatally injured.

Struck 19 times, including numerous blows to the head, he spent the 33 days it took him to die at the Hôtel de Boisy on Rue Saint-Antoine. In his journal, l'Estoile reports that the king came to see him every day. After he died, Henry had his head shaved so that he could keep his favourite's blond locks and also removed his earrings.

Jules Delpit

A major figure in the scholarly circles of the Bordelais region in the nineteenth century, Jules Delpit (1808-92) was known primarily for his prolific work in the archival field and for his involvement with many erudite societies (fig. n). After studying at the Collège Royal de Bordeaux and graduating in law from the École de Droit de Paris, he pursued his education at the École des Chartes, which provided this young man from the provinces with an entrée into the world of the "antiquarians", at that time scholars with multifaceted interests who studied monuments, sculptures, objets d'art, manuscripts, coins and more besides. His career initially took him to England on an assignment (under the direction of Augustin Thierry) to investigate the archives there. He returned to France in 1844 and took up residence in his native Guyenne, where he became one of the key figures in local scholarship, devoting himself in the main to the archives of Bordeaux. At this time he was living some thirty kilometres from the regional capital, in his wine-growing estate at Izon. It was here, in the house he had had built to his own designs, that Delpit accumulated a large number of written works - his library comprised some 400,000 items dating from the thirteenth to the nineteenth centuries - and also built up collections of medals, paintings, sculptures, and objects of every description.

After his death, his widow disposed of his library, initially selling a large part of it to the city of Bordeaux, and in November 1897 auctioning off the drawings, engravings and lithographs, along with the remainder of the books, in a series of local sales.

There is no mention of sculptures in all of these auctions. In 1996, Delpit's great-great-granddaughter, Catherine Delpit, drew up a catalogue of her ancestor's private collections as part of a master's dissertation and refers to this important marble head, supported by a photograph, under number 114. Describing the sculpture as a Tête d'homme couronné de lauriers, she points out that it was not sold in the sale of 15-23 November 1897 and that it formed part of a private collection. No light is shed on the circumstances in which this fragment of the Paris tomb was acquired by Jules Delpit, who bought principally at auctions in Paris and in his local region. It is altogether understandable that, having remained in a local collection for the intervening period, the head should resurface in the regional art market more than 20 years after publication.

The discovery of this sculpted head by Germain Pilon - considered by some to be the Michelangelo of the French Renaissance - is clearly of great significance in the history of sixteenth-century sculpture. Aside from a number of works by the master that can still be seen in churches in Saint-Denis, Paris, Châtellerault, and Le Mans, other pieces by Germain Pilon (and his studio) that are attested in historical documents and conserved in public collections remain highly fragmentary. In France they are split between the Louvre and the Musée de la Renaissance in Écouen; abroad, there are just two bronze cherub's heads in the Staatliche Museen in Berlin. No element identified as potentially deriving from the famous mausoleum of the Mignons, destroyed some ten years after its erection in the church of Saint Paul, has been catalogued. It seems that we are in the presence here of the only surviving element of this royal commission to have come to light to date, this "Triade éclatante", to quote the art historians, which made such an impression on the contemporary mind.

1 J. Rabel and N. Bonfons, Les antiquités [...] et singularités de Paris [...], Livre second, 1588.

2 P. de L'Estoile, Registre-Journal du règne de Henri III, vol. II (1576-1578), Geneva, 1996, p. 228.

3 F. de Birague, Les premières oeuvres poétiques, Paris, 1583.

4 P. de Ronsard, Les Oeuvres, Paris, 1584.

Works consulted:

P. du Colombier and J. Adhémar, "Nouveaux documents sur Germain Pilon" in Humanisme et Renaissance, vol. 6, no.3, year 1939, pp. 304-323.

E. Coyecque, "Au domicile mortuaire de Germain Pilon (10 février au 13 mars 1590)" in Humanisme et Renaissance, vol. 7, no.1, year 1940, pp. 45-101.

C. Grodecki, Archives nationales. Documents du minutier central des notaires de Paris. Histoire de l'art au XVIe siècle (1540-1600), vol. 2, Paris, 1985-1986.

Proceedings of the conference Germain Pilon et les sculpteurs français de la Renaissance, held at the Louvre under the direction of G. Bresc-Bautier, 26 and 27 October 1990.

C. Delpit, Un collectionneur bordelais: Jules Delpit (1808-1892), Bordeaux, Université Bordeaux 3 (history of art and archaeology master's dissertation), vol. III, 1996.

J. Boucher, "Contribution à l'histoire des Mignons (1578): une lettre de Henri III à Laurent de Maugiron" in Nouvelle Revue du XVIe siècle, vol.18, no.2, year 2000, pp.

113-126.

N. Le Roux, La faveur du roi, Mignons et courtisans au temps des derniers Valois, Paris, I. de Conihout, J.F. Maillard and Guy Poirier, Henri III mécène des arts, des sciences et des lettres, Paris, 2006.

Internet source: https: //fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jules_Delpit " data-desc-exceprt="

En savoir plus

A rediscovered sculpture by Germain Pilon possibly the head of Jacques de Lévis-Caylus, the best known of Henry III of France's favourites known as the «Mignons»

Important head of a man crowned with a laurel wreath, Carrara marble sculpted in the round.

A portrait of a young man with a somewhat gaunt face featuring a high, domed forehead, a long, straight nose, a mouth with finely drawn lips, a trimmed moustache and beard; open eyes with semi-circular upper palpebral fold, lashed eyelids with visible lacrimal caruncle, irises positioned beneath the upper eyelids, circumscribed by an incised line and with pupils centred on a point; forehead with exposed temples surmounted by curly hair; severed neck with chisel marks, revealing the cavity from a lead fixing.

Île de France, Paris, Germain Pilon (known 1540-died Paris 1590), after 12 July 1578/first half of 1579.

H_34 cm

On plinth.

(some light abrasion, tip of the nose restored)

An export certificate of the lot will be given to the buyer

Provenance:

- Ex-collection Jules Delpit (1808-92), Bordeaux

- Ex-collection, private, Bordeaux region

A head of such dimensions, that is to say over life-size, sculpted in extremely costly Carrara marble and, moreover, wearing a laurel wreath, could only be that of an illustrious figure connected with the court of around 1580. Indeed the physiognomy of the face links it to the reign of Henry III: the highly pronounced lobes above the temples, the curly, swept-back hair, the short, well-trimmed beard, the high cheekbones and the pointed chin recall the portrait of the monarch after Nicolas Hilliard, circa 1578 (fig. a).

This is evidently a portrait because despite being mildly idealised, the features remain individual, hence the pronounced lines of the cheeks, the distinctive development of the frontal bone, the vivacity of the gaze and the marked sensuality of the mouth. While possessing the character of youth, this face gives a strong impression of determination and daring.

The laurel wreath is a mark of distinction uncommon in sculpted portraits of the sixteenth century. It can, of, course, be found gracing the brow of monarchs such as the

Louvre bust of Henry II, completed between 1574 and 1579, and the equestrian statue of Charles IX in the same museum. Another example is the bronze bust of Henry III in the Wallace Collection, attributed to Germain Pilon. And to judge by the inventory drawn up after the death of this great French sculptor, in which a bronze head of a Religieux couronné de laurier is mentioned, the same honour seems to have been conferred on various prelates.

But what young person might be depicted wearing a laurel wreath? Clearly it could only be a personage belonging to the innermost royal circle, someone cut down in the prime of life in circumstances regarded as remarkable at the time. Only the favourites of Henry III known as the «Mignons» combine these qualities. This leads us to the notorious Duel of the Mignons of 27 April 1578, which claimed the lives of two of these, Maugiron and Schomberg, the same day, a third, Ribérac, the following day, and Caylus after exactly thirty-three days, when he eventually succumbed to his injuries. A few weeks later another favourite, Paul Stuart de Caussade de Saint-Mégrin, lost his life, in all likelihood murdered on the orders of the Duke of Guise.

It is known that the king was greatly affected by all of these deaths. To honour the memory of his closest favourites and in the intention of establishing a veritable cult in their name, he commissioned three tombs from his master sculptor, Germain Pilon, in July 1578.

The Tombs of the Mignons:

This commission given to Pilon by Henry III was the only one of its type and unfolded in two stages. An initial order was signed on 12 July 1578 for the tombs of Maugiron and Caylus but this was cancelled soon after, when the king decided to commission a third tomb for Saint-Mégrin. It had been agreed in the first contract that "Pillon has promised and promises to complete the aforementioned two sculptures and to deliver them in a perfect state" by the last day of December [1578]. It is known from another document that on 17 January 1579, master armourer Nicolas de Charenton was receipted for providing the sculptor with items of armour belonging to the late Saint-Mégrin, no doubt so that they could be used as a model for the kneeling statue. It can therefore be ascertained that by this date the mausoleum, or at least the tomb of Saint-Mégrin, the last to have been commissioned, had not yet been completed. That of Caylus was probably already finished given that the blocks of marble had already been selected by the signing of the first contract. There is a strong likelihood that these funerary monuments were installed in the choir of the church of Saint Paul in Paris during the course of 1579. Their existence was fleeting as they were destroyed by the people of Paris some ten years later, following the assassination of the Duke of Guise and another family member on 2 January 1589. The only depiction we have of them is an engraving by Rabel of 15881 (fig. b). In the eyes of the population, and against the backdrop of the ultra-Catholic atmosphere of the day, these luxurious tombs symbolised the presence of an ostentatious impiety at the heart of a church. Their destruction followed the ritual employed in the massacre of heretics, that is to say the cutting off of all the extremities, thereby explaining the good state of conservation of the marble head. If the sculpture of the kneeling figure was indeed thrown from the top of its mausoleum, its head had almost certainly been removed beforehand.

These sumptuous tombs commissioned by the disconsolate Henry III were admired by contemporary observers. Visitors came to see them when passing through Paris.

One such was the Dutchman Arnold van Buchel, who described them as "glittering marble and bronze tombs with marvellous marble statues of the three courtiers". The model for these funerary monuments - a tapering sarcophagus resting on an entablature and supporting the statue of the deceased kneeling with hands joined in prayer before a prie-dieu - was well used by Germain Pilon but here he gives his most magnificent version of it. Due to the luxurious materials used, the first two cost the substantial sum, for the day, of 3,500 crowns. Although this initial specification was cancelled, it is highly likely that the definitive contract for the three sepulchres, now missing, incorporated the same description. What stands out from this description is the use that was to be made of white and black marble, the inclusion of numerous decorative elements, such as bronze trophies and coats of arms, as well as a number of cherub's heads in white marble. The statues that surmount each tomb are described as follows: the "deceased sires praying, life-size in white marble and as life like as can be". By contrast with the ecclesiastical world, which preferred recumbent figures, the formula that had been favoured since the 1550s by the nobility had been the kneeling figure.

The brutal deaths of these young men belonging to a group of favourites very close to the monarch, and affectionately referred to by the king himself as "ma troupe", were much lamented. A number of poets, including illustrious figures such as Ronsard, Desportes and Jamyn, as well as the official preacher to the king, Arnaud Sorbin, composed sonnets and other verse works extolling Maugiron, Caylus and Saint-Mégrin. Pierre de l'Estoile, the famous chronicler of the day, reproduces these Sonnets courtizans à la mémoire des trois mignons in his diaries. 2 Certain lines speak of the tombs and the glorious laurel wreaths crowning the heads of the departed:

Il ne fault vous douloir, soubs vos tombeaux couverts

De mirte et de laurier, que vostre ame est allée

Des esprits bienheureux habiter la vallée, Perdant trop tost la fleur de vos printemps si verts.

Germain Pilon:

Although the name Germain Pilon remains firmly associated with the tomb of Henry II, commissioned by Catherine de Médicis, at Saint-Denis, it was under the reign of Henry III (1574-89) that the sculptor executed the majority of his works. Many were later destroyed, falling victim to the numerous outbreaks of unrest and destruction resulting from the civil, religious or seditious wars. Pilon was "sculptor to the king" from as early as 1558, and ended his days as "sculptor and architect in ordinary to the king". As a complete artist, Pilon exercised his talents in a wide range of materials: bronze, terracotta, stone, alabaster and marble. In particular he excelled at working the latter, translating into marble various effects more commonly found in a malleable material. It is notably in the field of funerary art that he impresses. A striking example of his genius is the recumbent statue of Valentine Balbiani leaning on one elbow (circa 1575) conserved in the Louvre.

The tombs of the Mignons date from the most fertile period in Germain Pilon's career as a funerary artist. During the fifteen years of Henry III's reign, the monarch commissioned no fewer than fifteen funerary monuments from him. And it was not by chance that the king chose Pilon for the mausoleum of his favourites. Not only was he the most experienced sculptor in Paris, he was also the natural choice of artist to commemorate members of the royal family as well as important servants of the state.

This marble head of a man is unquestionably the work of a great sculptor. Clearly in evidence are the qualities of an artist accustomed to portrait work and skilled in individualising the features, as evidenced by the vivacity of the gaze, the delicate modelling of the lips and the sensitive rendering of the cheeks, showing the creases in the skin. A number of comparisons can be made between the treatment of certain details and known works by Pilon or his studio:

The eyes: hollowed out lacrimal caruncle (Valentine Balbiani and the cherubs on her tomb, Louvre fig. c and d, soldier in the Resurrection of Christ, fig. e)

The ears: general shape, fleshy, detached lobe (The Parcae, Écouen, fig. f, Balbiani cherub, fig. g)

The hair: the shell-like curls with trepanned centres (Balbiani and cherub fig. h and i)

Caylus:

Of the three Mignons from the tombs, this marble head would seem to belong to the kneeling figure of Jacques de Lévis-Caylus (fig. j and j')

Louis de Maugiron, the youngest, at just 18 years of age, can be eliminated because he had lost an eye to an arrow in battle, earning him the nickname "le brave (or le beau) borgne" (the brave [or handsome] one-eyed man). Of Paul Stuart de Caussade de Saint-Mégrin and Jacques de Lévis-Caylus, both born in 1554, this elongated face with exposed temples and a mildly receding chin would seem to correspond to the latter. Although the highly idealised portrait by Quesnel (fig. k), depicting Caylus beardless, bears little resemblance to the marble head, the portrait in profile by Bracquemond (fig. l) is uncannily similar in its high, domed forehead, long, straight nose, receding chin and nasolabial and jugal folds that give shape to the cheek.

The pronounced upper temple area can even be observed in the portrait by Dumontier presumed to be of Caylus as a young man (fig. m).

Jacques de Caylus was reputed to be one of the most handsome of Henry III's Mignons. In the madrigal composed by the poet Flaminio de Birague to serve as the epitaph on the tomb of the Mignons, Caylus is described as follows:

Voyez Amour depaint en Adonine face

Voyés les rares traits, d'une divinité 3

Meanwhile Ronsard engages in a dialogue, asking:

Est-ce-ici la tombe d'Amour ?

Est-ce point celle d'Adonis

Est-ce Narcisse, qui aima

L'eau qui sa face consuma

Amoureux de sa beauté vaine ?

And the answer comes:

La beauté d'un jeune printemps [repose ici]4.

And Desportes, not to be outdone, offers lavish praise:

Quelus, que la nature avoit fait pour plaisir, Comme une oeuvre accomplie, admirable et divine, Portoit Amour aux yeux et Mars en la poitrine.

Jacques de Caylus was born of an ancient family. He was the son of Antoine de Lévis-Caylus, seneschal and governor of Rouergue, a great lord loyal to the king. At the age of 18, his father entrusted him with the delivery of a missive to the future Henry III, who, a year later, during his brief reign in Poland, conferred on the youth the office of Gentilhomme de la chambre du roi (Gentleman of the King's Bedchamber). Jacques de Caylus would never again leave the circle of the king. He fought alongside or for him, for example at the Siege of La Rochelle, confronted the Protestants at the Battle of Dormans (under the command of the Duke of Guise), and was taken prisoner by the Huguenots near Brouage in 1577 and held for three months. He therefore wears the laurel wreath in just recompense for his courage and as a symbol of the glory evoked by Birague in his epitaph:

Est-ce, que vous voiez sur son arc et sa trousse

Cent lauriers, vray guerdon des guerriers généreux, Et que vous ne croyés qu'un coeur si valeureux

Puisse ploier au ioug de la Cyprine douce ?

Upon his return to Paris, Caylus became embroiled in the feuds of the various factions. As a faithful servant of the king, he accepted a challenge to a duel issued by Charles de Balsac d'Entragues the Younger, known as Entraguet, one of the Duke of Guise's men, within the context of the famous Duel of the Mignons, which was fought not far from the Porte Saint-Antoine. Caylus was accompanied by his seconds Maugiron and Livarot. Whereas Entraguet escaped virtually unscathed, Caylus was fatally injured.

Struck 19 times, including numerous blows to the head, he spent the 33 days it took him to die at the Hôtel de Boisy on Rue Saint-Antoine. In his journal, l'Estoile reports that the king came to see him every day. After he died, Henry had his head shaved so that he could keep his favourite's blond locks and also removed his earrings.

Jules Delpit

A major figure in the scholarly circles of the Bordelais region in the nineteenth century, Jules Delpit (1808-92) was known primarily for his prolific work in the archival field and for his involvement with many erudite societies (fig. n). After studying at the Collège Royal de Bordeaux and graduating in law from the École de Droit de Paris, he pursued his education at the École des Chartes, which provided this young man from the provinces with an entrée into the world of the "antiquarians", at that time scholars with multifaceted interests who studied monuments, sculptures, objets d'art, manuscripts, coins and more besides. His career initially took him to England on an assignment (under the direction of Augustin Thierry) to investigate the archives there. He returned to France in 1844 and took up residence in his native Guyenne, where he became one of the key figures in local scholarship, devoting himself in the main to the archives of Bordeaux. At this time he was living some thirty kilometres from the regional capital, in his wine-growing estate at Izon. It was here, in the house he had had built to his own designs, that Delpit accumulated a large number of written works - his library comprised some 400,000 items dating from the thirteenth to the nineteenth centuries - and also built up collections of medals, paintings, sculptures, and objects of every description.

After his death, his widow disposed of his library, initially selling a large part of it to the city of Bordeaux, and in November 1897 auctioning off the drawings, engravings and lithographs, along with the remainder of the books, in a series of local sales.

There is no mention of sculptures in all of these auctions. In 1996, Delpit's great-great-granddaughter, Catherine Delpit, drew up a catalogue of her ancestor's private collections as part of a master's dissertation and refers to this important marble head, supported by a photograph, under number 114. Describing the sculpture as a Tête d'homme couronné de lauriers, she points out that it was not sold in the sale of 15-23 November 1897 and that it formed part of a private collection. No light is shed on the circumstances in which this fragment of the Paris tomb was acquired by Jules Delpit, who bought principally at auctions in Paris and in his local region. It is altogether understandable that, having remained in a local collection for the intervening period, the head should resurface in the regional art market more than 20 years after publication.

The discovery of this sculpted head by Germain Pilon - considered by some to be the Michelangelo of the French Renaissance - is clearly of great significance in the history of sixteenth-century sculpture. Aside from a number of works by the master that can still be seen in churches in Saint-Denis, Paris, Châtellerault, and Le Mans, other pieces by Germain Pilon (and his studio) that are attested in historical documents and conserved in public collections remain highly fragmentary. In France they are split between the Louvre and the Musée de la Renaissance in Écouen; abroad, there are just two bronze cherub's heads in the Staatliche Museen in Berlin. No element identified as potentially deriving from the famous mausoleum of the Mignons, destroyed some ten years after its erection in the church of Saint Paul, has been catalogued. It seems that we are in the presence here of the only surviving element of this royal commission to have come to light to date, this "Triade éclatante", to quote the art historians, which made such an impression on the contemporary mind.

1 J. Rabel and N. Bonfons, Les antiquités [...] et singularités de Paris [...], Livre second, 1588.

2 P. de L'Estoile, Registre-Journal du règne de Henri III, vol. II (1576-1578), Geneva, 1996, p. 228.

3 F. de Birague, Les premières oeuvres poétiques, Paris, 1583.

4 P. de Ronsard, Les Oeuvres, Paris, 1584.

Works consulted:

P. du Colombier and J. Adhémar, "Nouveaux documents sur Germain Pilon" in Humanisme et Renaissance, vol. 6, no.3, year 1939, pp. 304-323.

E. Coyecque, "Au domicile mortuaire de Germain Pilon (10 février au 13 mars 1590)" in Humanisme et Renaissance, vol. 7, no.1, year 1940, pp. 45-101.

C. Grodecki, Archives nationales. Documents du minutier central des notaires de Paris. Histoire de l'art au XVIe siècle (1540-1600), vol. 2, Paris, 1985-1986.

Proceedings of the conference Germain Pilon et les sculpteurs français de la Renaissance, held at the Louvre under the direction of G. Bresc-Bautier, 26 and 27 October 1990.

C. Delpit, Un collectionneur bordelais: Jules Delpit (1808-1892), Bordeaux, Université Bordeaux 3 (history of art and archaeology master's dissertation), vol. III, 1996.

J. Boucher, "Contribution à l'histoire des Mignons (1578): une lettre de Henri III à Laurent de Maugiron" in Nouvelle Revue du XVIe siècle, vol.18, no.2, year 2000, pp.

113-126.

N. Le Roux, La faveur du roi, Mignons et courtisans au temps des derniers Valois, Paris, I. de Conihout, J.F. Maillard and Guy Poirier, Henri III mécène des arts, des sciences et des lettres, Paris, 2006.

Internet source: https: //fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jules_Delpit " data-desc-exceprt="

Importante tête d'homme laurée en marbre de Carrare sculptée en ronde-bosse.

Portrait d'un homme jeune au visage légèrement émacié avec haut front bombé, long nez droit,...">

Importante tête d'homme laurée en marbre de Carrare sculptée en ronde-bosse.

Portrait d'un homme jeune au visage légèrement émacié avec haut front bombé, long nez droit,...

Déposer un ordre

Se renseigner

Vente

10/12/2018 00:00

10/12/2018 00:00

10/12/2018 00:00

10/12/2018 00:00

Vente

Vente

Lot n°1

Lot de deux bracelets

Adjugé 300 €

Lot n°2

Croix pendentif

Adjugé €

Lot n°3

Plaque-boucle

Adjugé 1 500 €

Lot n°4

Grande fibule

Adjugé 2 100 €

Lot n°5

Bague

Adjugé 7 000 €

Lot n°6

Importante bague en or et cornaline

Adjugé €

Lot n°7

Anneau pastoral de cisterien

Adjugé 550 €

Lot n°8

Bague en or

Adjugé 1 800 €

Lot n°9

Bague sceau

Adjugé €

Lot n°10

Bague en or

Adjugé 1 850 €

-

+

-

+